Good morning,

I remember sitting at the big wooden dining room table at my aunt and uncle’s lakehouse in Delavan, Wisconsin.

A smattering of cousins and relatives and my parents and I had just finished a game of Yahtzee or Monopoly.

We were now talking about what to eat next. This was probably 30 years ago.

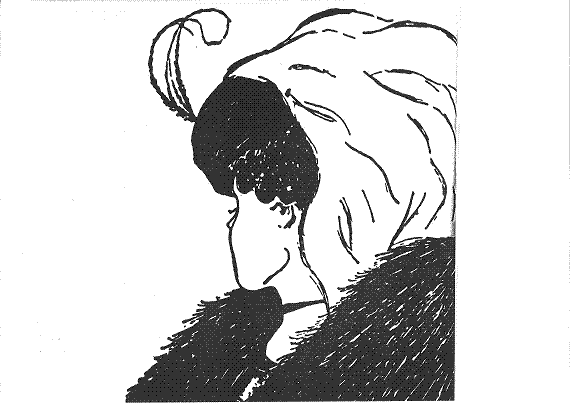

During this lull before dinner, I remember my mom bringing out a book (I did not remember the title of the book, but after some Googling just now I’m pretty sure it was Stephen Covey’s Seven Habits of Highly Effective People) and showing some of my cousins and me this picture and asking us what we saw:

Right away there were two camps: some of us saw a young woman with a chiseled jawline looking over her right shoulder; some of us saw an older woman looking down with her mouth slightly agape. My cousins and I argued back and forth about which one we saw, until eventually, my mom asked us if it’s possible that both perceptions of the woman in the illustration could be true.

At that time, Magic Eye books were in vogue. I remember having a small stack of them in my family’s living room and was somewhat adept at resting my eyes until I saw the 3D images arise from the swirls of black and white computer-generated pages. She told us to rest our eyes and use the skills from the Magic Eye books to patiently see the other version of the woman.

It took a few minutes, but eventually all of my cousins and I were able to experience the “Whoa!!” moment that comes with a little patience and putting aside initial perceptions while looking at this image.

This was one of the more powerful and memorable experiences I had as a child; so much so that I did this exercise with my middle school Social Emotional Learning students a few years back and essentially replicated what my mom facilitated for my cousins and me when we were around the ages of 9-12. I loved being the facilitator of this paradigm shift, watching my students shift from being convinced that they were right, and then giving themselves a few minutes to see that with this exercise, there is more than one way to see things. I witnessed big smiles and ripples of joy course through them, an unbridled energy as the result of having a new perspective after being certain something couldn’t be true.

I was reminded of this paradigm shift exercise again the other day while reading a new book by the esteemed theater director Kimberly Senior. Titled What Would a Person Do? Thoughts on Directing and Living, Senior’s slim but mighty volume contains a few dozen chapters that serve as daily reflection-type readings. She invokes a personal anecdote about her life as a theater director and then extrapolates it into something universal that most anyone, whether they work in theater or not, could relate to.

Senior explains the title in her book’s introduction:

“We encounter a moment in rehearsal where an actor is faced with the challenge: I have this cup of coffee in my hand, but I also want to hug this person. Stumped by this obstacle, the actor turns to me for guidance. I look at this brilliant actor, who I love dearly, and simply ask, ‘What would a person do?’

This collection of tiny ‘thoughts’ is drawn from my experiences in making and teaching theater where the question ‘What would a person do?’ is a constant refrain which has led me to write a book that is not exclusively for theater makers but also for those complex humans who we so often study. My true passion lies in human behavior and all of my work is an exploration of that.”

Some of the cleverly-named chapter titles include: “Chekhov’s Dope,” “Note Behind the Note,” “My Invisible Suitcase,” and “You’re Not Who You Used to Be.” I could probably write a short essay on each of these chapters, but the one that jumped out at me the other day is on page 88, titled “Having It All.”

Senior writes:

Page 88 – Having It All

I’ve been a freelance director now for more than half of my life. That means for more than half of my life I’ve been my own boss. I control my calendar, I live by my ethics, I decide which jobs I take and which I don’t. I even choose my collaborators most of the time. I travel all over the country, living my best life in corporate housing, using ClassPass to try out every fitness cult on the planet, and have had lovers in multiple cities. My children are truly being raised by a Village and travel to see their mom at work, a resilient and dynamic leader who tells stories that change lives and create conversation in multiple markets.

I even get to continue growing as an artist, trying out new mediums, such as scripted audio podcasts and directing comedy specials. I’ve directed everywhere from a church basement to Broadway and worked with some major talent, famous and not yet famous. All while being represented by one of the best agents in the business (Chris Till at Paradigm, who is as eager to dream with me as he is to reality check me.) I’m supported by an incredible union, 2200 strong, where I am in solidarity and celebration with the brightest minds in our field. Life is abundant.

I must look like I have it all.

Here’s another version of the story. I’ve been a freelance director for more than half of my life. That means for more than half of my life I haven’t known where my income is coming from, if I’ll get paid on time, and what I will earn year to year. I have to take most jobs offered to me because of this scarcity mindset. And sometimes when I’m working on five projects all at once I’m also chasing down checks and can’t pay my bills…

Page 89

...even though I’ve earned thousands of dollars, I can’t seem to get anyone to pay me. My union protects me but institutions are so slow to get my contracts signed and it’s in my best interest to adhere to calendar deadlines because the show running behind is a detriment mainly to me. So I started working without a contract, which also means without a paycheck.

I work inside institutions that occasionally have toxic cultures that I inherit and have to navigate for myself and the artists for whom I feel responsible. Sometimes leadership in those institutions have different ideas than I do and I have to figure out how to honor their notes and my vision. I feel like I have thirty different bosses all at once, all of whom think I am available 24/7 to speak with them and think they’re my most important project.

Sometimes the housing has cockroaches, or no internet, or the funk of thousands of artists before me. And the “gym” is a treadmill that occasionally works and mismatched free weights. The nearest grocery is a thirty-minute walk, or I can sign out the shared ’84 Chevy Impala.

Meanwhile, my children need me. They need new shoes, a haircut. They need homework help. They need structure. The Village is cool, and all, but the Village has also ruined my favorite cast iron, gotten into fender benders in my car, broken vintage cocktail glasses, and overspent on groceries. And the village isn’t Mommy. The Village can’t navigate heartbreak and comfort in quite the same way, or enforce that suitcase of values quite like I can.

Page 90

Plus, I’ve got my own mother, the model Stay-At-Home-Mom, who is worried and checking in with me and checking in on the kids and I feel like I’ve failed her, and failed my kids, and am failing myself. And my actors don’t really like each other, and I don’t really like the play, and the Artistic Director is up my ass, and all I have is pickles and mustard in my company housing.

Always a great moment to remember I’m professionally single, that I don’t have a real partner, that help is NOT on the way. That I hold the weight of it all.

But I have it all, right?

“Be kind to everyone and fight a great battle.” Yep. True. Every maxim rings true. “The grass is always greener.” Like in any profession, any life, there are good days and bad days. I think about one of my favorite children’s books, Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day. We all have those days.

I’m learning to not hide these days. I always feel guilty complaining, asking for help, asking for comfort. Because I have so much. Lately, I’ve realized that sharing these feelings also helps others. It’s rare that we’re all having a bad day at the same time. There’s probably room to reach out to your partner, best friend, mentee, mentor, neighbor. It feels good to help someone hold their burdens. It also feels good to know that we’re not alone on these kinds of days. Weeks. Months.

Page 91

Also, go to therapy. Everyone should. Not to solve a “problem.” It’s time that’s just for you to talk about you because you are literally paying someone to listen. And if they know you on a good day, they’ll be better able to help on a bad one.

So, yeah, I guess I do have it all. I have an incredible, ever-changing career that I bust my ass to do. I have two wonderful, curious, hilarious kids. I have friends and collaborators who I’ve grown with for decades. And I’ve got me. This body, this mind, this heart, this life. I’ve got it all.

Over the years I’ve had many reminders that it’s often my perception of reality that’s the problem, not reality itself. In addition to the image from Covey’s book, Senior’s writing reminds me of the only quote I remember by Wayne Dyer via one of his self-help CDs my first boss out of college gave to me in order to help with my sales career. (Why are self-help and sales so closely related? Maybe because it’s one of the most ego-bruising jobs imaginable… note: save this topic for a future letter). Dyer’s simple and memorable refrain has stuck with me for over 20 years: “When you change the way you look at things, the things you look at change.”

Senior’s chapter about having it all exists in the same realm as the above illustration and Dyer’s pithy aphorism.

And I wonder: How come if I already know something I still need reminders? It’s probably just the human condition (sigh, again), and it reminds me of another quote, this one by the late great Quincy Jones, apropos to making music:

“Nadia Boulanger, my former teacher in Paris, used to tell me, 'Quincy, there are only 12 notes. And until God gives us 13, I want you to know what everybody did with those 12.' Bach, Beethoven, Bo Diddley, everybody...it’s the same 12 notes. Isn’t it amazing? That's all we have, & it's up to you to create your own unique sound through a combination of rhythm, harmony & melody. Since music is ever-changing, it's impossible to get the same result twice, & I'm always fascinated to hear the different outcomes that you can create with only 12 notes.”

Dyer, Senior and the person who made the illustration (W.E. Hill) are all using the same notes to make different metaphorical songs with the same message… I guess that similarly to music, in this case a psychological message can take the same notes and sing in ways that resonate with different people and at different times of their lives. Bravo to the writers, creators and thinkers who share their various forms of music.

Until next time,

Matt